The Blog

True North: Expanding Our Vision

Change is rarely simple. Sometimes, it’s catalyzed by discomfort—by pressure, frustration, or the realization that what used to work no longer fits. But if we’re paying attention, change can also offer a powerful opportunity to reflect, realign, and step forward with...

It’s Time to Renew Our Vows: Revisiting Commitments to Social Change Work.

I was leading a session the other day and during a group reflection activity I decided to share with the group the news that I’m getting married this summer. I surprised myself by sharing it; I tend to be a private person, and as a woman in professional spaces—where...

Meeting the Moment: Acceptance as the Path to Transformation

I’ve been grappling for the last month and a half with the nature of what shouldn’t be. This shouldn’t be our country’s leadership. I shouldn’t have to do important work in quiet. Human beings shouldn’t have to feel erased. No one should be born into a world where...

Bend Without Breaking: Adapting as a Collective

Written by Erin Dunlevy, VP and Consultant, True North EDI “Change is coming – what do we need to imagine as we prepare for it?” (p. 58, Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown) For many of us on TikTok, these last few weeks have felt like the final pre-summer weeks...

Old Tactics, New Fronts: Understanding DEI Bans, Erasure, and the Fight for Equity

Written by Cardozie Jones, CEO and Founder, True North EDI The political landscape in the United States is shifting, and with it, so are the boundaries of what is acceptable to discuss, teach, and prioritize in workplaces, schools, and public life. Diversity, Equity,...

From Pedagogy to Practice: Lessons from Education in Divisive Times

Written by Cardozie Jones, CEO and Founder, True North EDI As a consultant and facilitator, my work centers on driving organizational and institutional change, specifically supporting those striving to align their aspirations with their actions to create more just and...

Joy as Resistance: Accepting the Challenge During Challenging Times

Written by Cathleen Antoine-Abiala Over the past few months, I've spent much of my downtime contemplating. Be it about the state of our country, the election, or the ongoing conflicts and humanitarian crises around the world. I know I'm not alone in feeling...

Beyond Strategy: How Organizational Culture Fuels Lasting DEI Change

DEI is often talked about in terms of aspirations and operations. Here’s the thing we want to do, and here’s the way we’re going to do it. A solid infrastructure in the form of a DEI committee, committed leadership and the guidance of a reputable DEI consultant should...

From Vision Loss to Visibility

Recently, I took to my personal social media to share some experiences and needs that are emerging as I navigate my journey with vision loss. In 2011, I lost all vision in my right eye after a surgery to repair a retinal detachment. In 2016, I was diagnosed with...

A Values-Based Approach to Conflict

Take a moment and think about how you were raised to behave during moments of conflict. When you had an argument with the people who raised you, what happened? Did those arguments look different or similar to the way conflict unfolded in your friendships as a young...

Navigating Imperfection: Language and Censorship in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

I recently found myself on two conference calls with two separate clients, both of whom I’ve worked with for years and take deep pride in the work we’ve been able to accomplish together. Both organizations focus on specific geographic areas in which their work...

DEI as DNA

In our recently launched newsletter The Compass, we talked about how this is a pivotal moment for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Efforts to dismantle DEI initiatives are at an all-time high, and yet, employee commitment to DEI remains high as well. For younger...

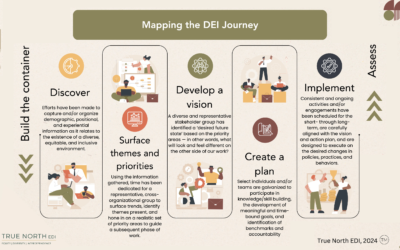

Map Your DEI Journey: 3 Key Insights

This month True North EDI hosted our first webinar of 2024, “Where do we go from here? Mapping the DEI Journey,” and the turnout and response was fantastic! It’s always wonderful to uncover and present a topic that resonates with so many. If you missed it, don’t...

6 Coaching Insights for Today’s Leaders

This summer, True North EDI’s Cardozie Jones and Erin Dunlevy offered complimentary coaching sessions to 20 emerging and established leaders across different sectors. We recognize that access to our services isn’t a given, so we are committed to doing what we can to...

The truth about emotions and leadership

Written by Jason Sirois I was recently invited to a dinner party with friends where the topic of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in the workplace came up. One of the hosts, a leader in his company, shared that the company was in the middle of a DEI staff...

What’s Missing is Consent

Last week DEI strategist, consultant and best-selling author Lily Zheng reacted (lovingly) to a LinkedIn post referring to a Forbes article by Aparna R. about misleading DEI reporting. Lily Zheng (who uses they/them pronouns) expressed support for the ideas presented,...

George Floyd’s Impact on the DEI Landscape

Legacy can have different meanings for each of us, but for most people, it's important to know that they have made some sort of impact on the world, whether big or small. While we may each be, as Elton John sings, a candle in the wind, I truly believe most of us seek...

Nurturing Meaningful and Responsive Partnerships

Over the past year or so, I've had the privilege of collaborating with incredible individuals and organizations who have shown a genuine interest in understanding the values, approach, and possibilities that come with partnering with True North EDI. It has been an...

DEI is intervention, not a cure

A few weeks ago, comedian and social commentator, Jon Stewart had some strong words for the DEI industry. Speaking with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria (clip from CNN here - about 2mins in), Stewart argues that so-called “diversity and equity” efforts are, “a salve to pacify and...

Then Came the Eye Roll: Skepticism in DEI

At a recent social event, I had the rare and exciting experience of being invited into an impromptu conversion about Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI). Our host introduced me to a handful of people and we started traversing the classic low-stakes conversation...

Bridging the generational rifts in Equity work

As with any community, the ways in which we engage one another can lead to the building of bridges or ensure the creation of walls.

New Year. Endless Possibilities

Last year, True North EDI honed in on four core values that represent both our internal and external approaches to community and change. Those values are Illumination, Creativity, Joyful Orientation, and Grace. When our team met at the end of the year to celebrate...